The more one is exposed to art, the more the patterns of existence reveal themselves. Various photographers today concern themselves with stretching the medium. I continue to believe there is a place for “traditional” photography, exploring like Giacometti a particular subject, in its myriad and endless permutations.

|

In 1927, Alberto Giacometti sculpted The Couple, a bronze case symbolizing, if more abstractly representing, a man and a woman, borrowing from more primitive or tribal work. The Museum of Modern Art in New York notes of this piece that “[t]he pairing of male and female figures announces what would become one of Giacometti's great, lifelong subjects: the encounter between men and women, life and art.” I have converted it to a black and white image to emphasize its detail, not its color, and allow comparison with the second image. They struck me as clearly a couple but who are remarkably disconnected as they each focus on their phones. Nonetheless, they are in proximity but also disconnected from each other.

The more one is exposed to art, the more the patterns of existence reveal themselves. Various photographers today concern themselves with stretching the medium. I continue to believe there is a place for “traditional” photography, exploring like Giacometti a particular subject, in its myriad and endless permutations.

10 Comments

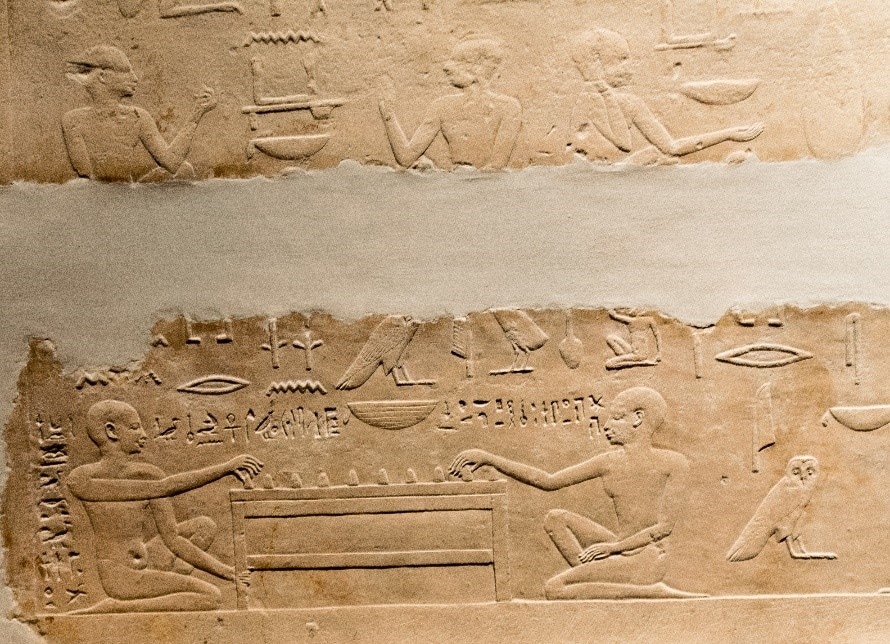

With the advent of the negative image and the introduction of photography in 1839, early photographers sought to establish photography as a legitimate art. Part of that movement entailed Pictorialism, where photographers staged scenes that evoked classical painting and photographed them. Eventually, the groups known as photo-secessionists moved towards more realism in photographic subject matter, taking advantage of the unique aspects of the photograph and the camera rather than trying to force the square peg of the photographic image into the round hole of painting. In other words, photography was its own medium and did not need to imitate other forms of art. There is value to the photographer in viewing paintings of all movements as well as sculpture and other art forms. Subject matter, composition, and how an artist uses a particular medium are informative. Which brings me to Egyptian art. On a certain level, one can discern elements of street art in Egyptian wall painting and objects from tombs. This image which I photographed at the Walters Art Gallery in Baltimore was part of the Egyptian collection depicting "Daily Life In Ancient Egypt.” This image shows two men playing the board game senet. This scene included other games players and musicians and was presumed to be a bas relief on the lintel of a doorway in the tomb of Ankh-ef-en-sekhmet. Look at this carefully. The man on the left has his left hand grasping the table leg as he reaches to make a move just as, apparently, the man to our right is in the process of perhaps finishing his move with his right hand. This man’s left hand is resting on his leg. Without too much of a stretch, we see one man, perhaps tense and maybe losing, and the other man, relaxed and perhaps winning. Artists generally make choices. Both are right-handed, apparently, but Egyptian art was about showing the entirety of the human form—why not have one left-handed and one right-handed, with the free hands in more symmetrical position? Both seem to have a trace of a smile on their faces as well. Perhaps the best answer is the artist sought a more natural depiction of daily life as it was actually lived. In this small detail, we come far closer to these two people in the time frame of 550-525 BC, within the Egyptian Late Period of 500 to 450 BC. Compare the Egyptian players with these two chess players in Atlanta, Georgia. Neither is touching a piece, but both are focused on the board. Their hands rest on their legs. It is a scene composed similarly to the Egyptian one, essentially two game players and a board, not looking at each other but at their board and contemplating their moves. What I find remarkable is that these two sets of players are separated by some 2500 years, and we can find common ground in human behavior. The street photographer in particular, searching for evidence of daily life in the contemporary city, finds an example of composition and human interaction in Egyptian art. The more we are aware of human behavior across the centuries as depicted in art, the more likely we are to recognize it in contemporary life.

I have been reading about distinctions between street photography and documentary photography. Certainly, there is overlap. Without attempting to repeat or develop the theoretical differences, we can synthesize the essential difference as this: documentary photography is meant to be objective in order to show its subject as a more permanent feature, whereas street photography is more subjective, capturing a moment that comes and goes and often has elements of whimsy to it. Both capture a sense of place. The key in photographing a city is to see beyond the iconic subjects, and look for the shot that captures character.

The image shown above was made in Belfast around Shaftesbury Square as I was heading towards the University Quarter. I like barber shops, as a contrast to the hair salons that lack the texture and look of the barber shops. I saw the head of a man, apparently waiting for his turn—but with a mainly bald head and a short fringe around it. With tight cropping to retain the elements of the barber shop to fix its identity, and close enough to show the head but leaving in the small reflection to draw the eye. The point of the photo is to capture a whimsical moment—a man in a barber shop—and I converted it to a black and white image for effect. Black and white enabled me to focus on the man and his head contrasting with the barbershop. Color would have been too distracting. These details and moments of life are what capture the essence of the city. It is easy to get overwhelmed when you have limited time to photograph a new place. I’d been to Belfast before and was on my way to cover an area I’d given short shrift to previously. You need to be aware, though, of what is around and fortuitous, and not be a prisoner of the map and the “must see” designations. |

AuthorSteven Richman is an attorney practicing in New Jersey. He has lectured before photography clubs on various topics, including the legal rights of photographers. His photography has been exhibited in museums, is in private collections, and is also represented in the permanent collection of the New Jersey State Museum. Archives

December 2022

|